Our content features commercial links to our products, committed to transparent, unbiased, and informed editorial recommendations. Learn More

What Makes Sword-Wielding Historically Accurate?

NO AI USED This Article has been written and edited by our team with no help of the AI

Many seek to learn sword wielding from TV shows, movies, stunt shows, and renaissance fair performances. Unfortunately, most of these depictions of sword handling are historically inaccurate, leading to several misconceptions about sword combat. While we cannot expect performance art to be as good as martial arts, it is interesting to learn how real-life warriors wielded swords in life-and-death battles.

Let’s debunk some myths and misconceptions about swordplay and what makes sword-wielding historically accurate.

Myths and Misconceptions About Sword Wielding

The abundance of misinformation about the reality of sword-wielding comes from misrepresentation in popular media. These include how sword-wielding men used their blades in actual combat, how real swords performed, and many other unrealistic aspects of a sword fight.

Myth # 1: Medieval swordsmen wielded extremely heavy swords.

Historical swords used in actual fighting were lightweight, well-balanced, and maneuverable. One-handed swords weighed an average of 2 to 4 lbs while two-handed swords about 3 lbs or more. Using extremely heavy swords would be impractical in actual combat as it would cause its wielder to be slow in changing directions.

Myth #2: Parrying or blocking with the sword’s cutting edge was common.

Parrying the slashing blows with the edge of a sword would damage or break the blade. Instead, swordsmen defended by hitting the incoming blade against the flat. In the medieval and Renaissance periods, swords were relatively expensive, so historical warriors did not use edge-on-edge parrying for defense.

Myth #3: Medieval knights used swords to cut through plate armor.

While chain mail was not immune to slashing cuts, slashing full plated armor with a sword was futile. Therefore, thrusting the gaps in plate armor with sharply tapered swords became the primary sword technique instead of cutting through it. Also, armored warriors were not immune to melee weapons.

Myth #4: Medieval knights wore too heavy armor on the battlefield.

There were various types of plate armor for mounted or foot combat, but they were all well-balanced and did not impair mobility. Even if the battlefield armor weighed around 45 to 55 lbs (20 to 25 kg), its weight was evenly distributed all over the body. Some tournament armor was even heavier, but was not used on the battlefield and was only worn for a limited time.

Myth #5: The skills of wielding swords eliminated the need for grappling and wrestling skills.

While a sword certainly helps a swordsman to fight and protect him from attacks, an opponent could always get close to disarm or throw him. Hence, a swordsman had to be capable of defending himself against his opponent by doing the same. Until around the 1700s, all sword fighting involved grappling and wrestling.

Myth #6: The samurai sword katana cut through European military swords in combat.

There is no evidence that a sword fight between samurai and Renaissance-period European swordsmen resulted in a sword being cut. Although there was a Dutch account from 1669 describing a smallsword that was cut into two, it was not a sword fight and the smallsword was set up in a stationary manner in a temple in Japan.

Also, cutting a smallsword is not a significant feat as it has a narrow and slender blade which could snap when bent with bare hands. It was a civilian weapon used by unarmed duelists and not a military sword for cutting.

What Makes Sword-Wielding Historically Accurate?

A historically accurate sword fight follows the forms and techniques in historical fencing manuals. Unlike stunt fighters and stage combatants, martial artists wield swords like historical warriors.

Sword-wielding involves well-executed motion and coordinated footwork.

Contrary to popular belief, wielding a sword is not just about having a sharp weapon and physical strength. In swordsmanship, sword-wielding involves having a proper grip, well-executed motion, strength, speed, and footwork. Swordsmen also employ correct postures and coordinated body movements.

Sword movements are not flashy.

Sword fights between skilled swordsmen are not flashy—but instead subtle and intense. They don’t appear choreographed or rehearsed. These fighters are difficult to watch, as their strikes are fast and unpredictable. They do not use wide and long strikes, as these are slow and create openings for the opponent to attack.

Swordsmen don’t stand still in a sword fight.

Historical fencing manuals tell fighters to be in constant motion—but it does not imply constantly circling each other. A good swordsman moves fluidly and does not hesitate to get closer to the opponent. Unlike modern fencers, historical swordsmen did not fight in a straight line. Also, a trained swordsman will not strike from a distance that is too far from the target.

A skilled swordsman does not spin in sword fights.

When sparring, swordsmen attack and counter an attack. So, turning around would only leave one’s back exposed and unprotected against an attack. Also, spinning won’t add extra force to a sword strike.

A swordsman attacks his opponent—not his sword.

A skilled swordsman tends to aggressively hit his opponent or keep him busy defending. On the contrary, an untrained fencer relies on parries and holds the sword in front to protect himself. Historical fencing manuals instruct not to stay defensive. Instead of just hitting the weapon, a swordsman must displace the opponent’s strike with a counterstrike.

Sword-wielding involves some grappling or wrestling.

Grappling and wrestling were often employed in medieval and Renaissance sword fighting. They utilize joint locks, throws, wrist locks, kicks, and even empty hand strikes. Some also seized an opponent and trapped their weapon or immobilized them. These also apply to earlier forms of cut-and-thrust swordplay and rapier fencing.

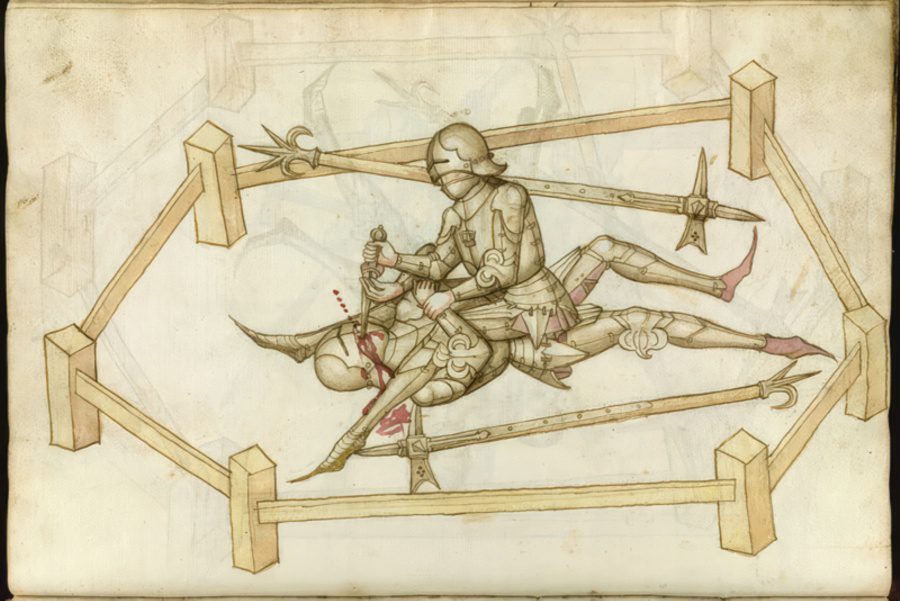

Armored combat employs a half-swording technique.

The half-sword technique grips the weapon halfway up the blade with one hand while the other hand holds the grip, giving the swordsman better control of his thrusting attacks. If he is fighting in armor yet using slashing with a sword, he may not fully comprehend the historical use of the weapon.

The goal is to end the sword fight as quickly as possible—not put on a show.

In sword fights, a skilled swordsman tends to strike first or use counterstrikes. Efficient strikes help to end combat quickly as an inefficient strike only gives an opponent another chance to defeat him. Still, sword-and-buckler fighting tends to last longer than combat with swords alone.

Why Is Sword Wielding in TV and Films Not Historically Accurate?

Sword-wielding warriors are everywhere, from the Game of Thrones to The Witcher and Star Wars. However, the popular media is not under obligation to educate and correct mistaken beliefs on sword-wielding.

From weapons to costumes and settings, there are several films with a medieval theme where swords including longswords, rapiers, and ninja swords were held and manipulated in ways which are never seen in role-playing or video games and anime.

Here are among the reasons why movies get their facts wrong about sword-wielding:

Sword-wielding actors and stuntmen are not martial artists.

Unlike martial artists who train in swordsmanship, many actors and stuntmen had never held a sword. Besides not having in-depth training in cutting, slashing, and footwork, they may only have had a few weeks to train for some sword-fighting scenes. Also, theatrical fencers are not required to show the historical methods of sword-wielding.

Sword-fighting scenes are choreographed.

Choreography makes a sword fight more dramatic and entertaining. Stunt fencers create an illusion of combat instead of following historical sword combat teachings.

Choreography has created some of the most entertaining sword fights in films, including those in The Princess Bride, where the actors and actresses performed all the swordplay scenes themselves. Besides learning to fight with both hands, they also studied each other’s duel choreography.

Some fight directors mix several martial arts instead of using a single fighting style.

In Highlander: The Series, the fight director incorporated various techniques in sword fights, resulting in the television series using weapons that were never seen in history. He utilized the Western infantry and cavalry saber techniques, Kenjutsu, Iaido, Pencak Silat, and so on. In some instances, fight directors also use sword techniques based on historical manuals, though the outcome would depend on the choreographer’s skill and the actor’s ability.

Sword fights had to be dramatic yet safe.

The choreography of sword fights must allow the audience to follow the action visually and dramatically—or they will lose interest. Stunt fencers prefer exaggerated motions for entertainment. This distorts how fighters move in combat and how swords were used safely. Hence, the agility, force, and physical actions are also limited.

The swordplay in films is highly technical.

The swordplay in films also considers the specific camera shots, space, lighting, and such. For instance, an actor would not swing his sword to avoid hitting the hanging chandeliers, furniture, and marble walls. More than that, sword fighting scenes are designed to tell a story, such as the beginning or resolution of conflicts between individuals or factions, rather than employing accurate historical techniques.

Historical Facts About Sword Wielding

Sword-wielding techniques evolved to meet the military needs of the time. Some were more suited for thrusting, while others utilized more slashing attacks. However, sword designs and fencing styles varied from culture to culture.

The Vikings used their swords primarily for slashing.

The Viking sword served as a dueling weapon and utilized slashing attacks. In fact, hacking blows were the typical fighting technique of the Vikings. Unfortunately, no surviving manual on its use exists, so many martial artists explore how a Viking warrior would fight with his sword. Also, historical reenactments do not replicate the actual combat as their off-target areas would have been the targets in a real sword fight.

Thrusting was the preferred means of sword attack against plate armor.

In armored swordplay, thrusting became the primary form of attack as cutting techniques were ineffective. An armored fighter was susceptible to some specialized fighting techniques, such as half-swording, in which the sword is held by the blade, as if it was a poleaxe or short staff. The technique allowed bludgeoning with the hilt, trapping, and disarming.

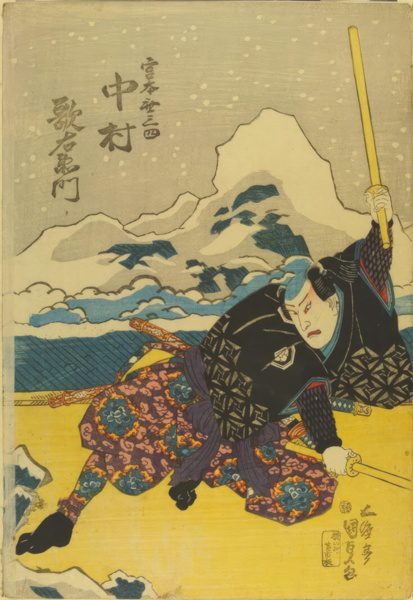

Some swordsmen wielded two swords in combat.

Japanese swordsman Miyamoto Musashi became known for his skill in double swordsmanship. He invented the nitō ichi-ryū, a fencing style with two swords, and wielded the katana and the short sword wakizashi.

In most illustrations, he is often portrayed as a dual wielder, using two wooden swords called bokken. The legendary swordsman was undefeated in 60 duels including the one with his rival Sasaki Kojiro, in which he only used a wooden practice sword.

Early fencers utilized a parrying dagger with rapier.

The rapier was a single-handed sword that utilized the point for thrusting. Without a shield or armor worn in battle, the early rapier fencers used a dagger held in the left hand to block or parry an attack. In Spain, the dagger was known as maingauche, which often matched the rapier design. Eventually, most of Europe favored parrying with the sword alone and discarded the left-hand parries.

Conclusion

Sword-wielding warriors in television series and films spark interest in swordsmanship. While sword fighting scenes in popular media are creative and entertaining, they are often historically inaccurate. Today, many martial arts practitioners reconstruct historical sword fighting methods.