Our content features commercial links to our products, committed to transparent, unbiased, and informed editorial recommendations. Learn More

Heavy Swords: Facts, Myths, and Misconceptions

NO AI USED This Article has been written and edited by our team with no help of the AI

In the hands of a skilled warrior, a sword could sever limbs and pierce through the gaps in armor. Many believe that medieval and Renaissance swords were extremely heavy and crude weapons. However, this misconception likely stemmed from a lack of knowledge regarding their historical background and experience with surviving examples.

Let’s uncover the myths and misconceptions about historical swords and explore how heavy they actually were.

How Much Did Historical Swords Really Weigh?

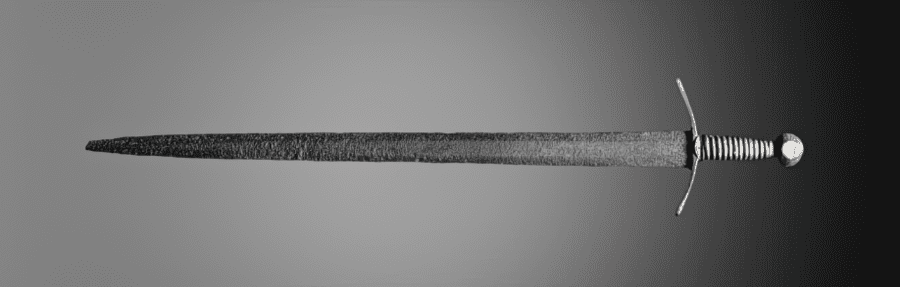

Historical swords that were used in combat were lightweight and maneuverable. Most single-handed swords had an average weight of 2 to 4 lbs., while the longer, two-handed swords, called the “grete war sword,” weighed over 3 lbs. Rapiers also weighed around 2 to 3 lbs., with most of their weight concentrated at their hilts.

Great swords, especially the German zweihander, weighed far lighter than they looked. The Landsknecht battlefield weapon had an average weight of 5 to 7 lbs. despite its overall length of around 150 to 175 centimeters (59 to 68 inches). Also, the Scottish Highland claymore weighed about 5.5 lbs.

On the contrary, bearing swords were often heavier, such as the ceremonial version of the zweihander, weighing around 10 to 15 lbs. Unfortunately, they are sometimes erroneously cited as actual fighting weapons, ignoring the fact that they have an impractical size and weight for combat. Many were also blunt-edged and poorly balanced for efficient use.

Heavy Swords in History

Historical fighting swords were lightweight and well-balanced. Some swords had relatively heavy blades, but that does not mean they were unwieldy and enormously heavy. Swords designed for other uses such as parades, ceremonies, or execution, may be heavier, but they are not fighting weapons.

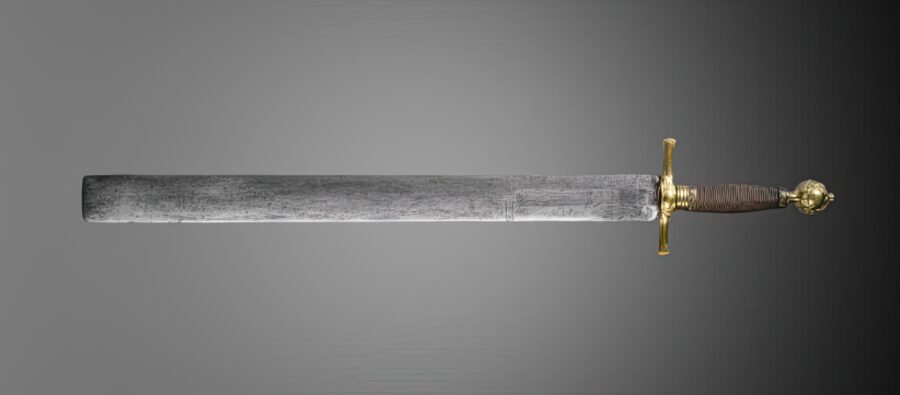

1. Executioner’s Sword

An executioner’s sword was well-balanced for decapitation, not for combat. Back then, being executed with a sword was considered less socially demeaning and more merciful than other methods. An executioner’s sword had a heavy, blunt-tipped blade and weighed around 5 lbs. However, its classic form did not appear until the Renaissance. Typical longswords were also capable of decapitating heads with one cut, as described in manuscripts.

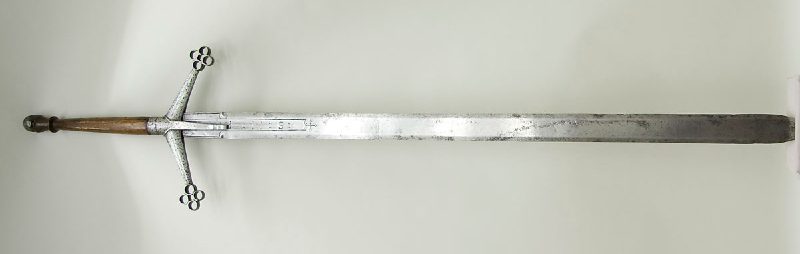

2. Claymore

The Scottish two-handed sword claymore served as a weapon for warfare from the 15th to the early 17th centuries. It is most recognized for its downward quillons ending in quatrefoils. Some museum examples had an overall length of around 140 centimeters and an average weight of 5 lbs. (2.2 kg). The Scots traditionally carried it on their backs.

3. Zweihander

The zweihander, meaning two-hander, was a specialized infantry weapon. Although large, measuring 59 to 68 inches overall, the German two-handed great sword only weighed about 5 to 7 lbs. The doppelsöldners or double-pay men used the zweihander to break up infantry formations.

When they lost their practical use on the battlefield, they served as parade swords or paratschwerter, designed for carrying in parades and ceremonial processions. Unlike the battlefield version, these bearing swords were too huge and heavy, weighing about 10 to 15 lbs.

4. Odachi

The Japanese sword odachi, also known as nodachi, had an extremely long blade. Fighting examples typically had a blade length over 90 centimeters, about 120 to 150 centimeters (47 to 59 inches). However, some historical records cite examples around 175 centimeters (68 inches), which was as tall as its owner’s height.

During the Nanbokucho period, from 1336 to 1392, the samurai used the odachi when fighting on foot and horseback. However, the longest and heaviest examples only served as a votive offering to the shrine and were never used for combat. The Norimitsu Odachi, created by swordsmith Norimitsu of Osafune, measures about 377 centimeters (148 inches) and weighs as much as 31.97 lbs. (14.5 kg).

Myths and Misconceptions About Heavy Swords

The misrepresentation of swordplay in popular media led to countless myths and misconceptions about sword’s weight and its historical use. Many films, anime, and fantasy games depict wildly intense sword fights where warriors wielded their swords using exaggerated movements. Historical reenactments and Renaissance Fairs also often misrepresent the reality of sword fighting.

Here are the most common myths and misconceptions about swords and the facts behind them:

Myth #1: Medieval and Renaissance swordsmiths did not have the technology to produce lightweight, quality swords.

Medieval steel blades varied in carbon content due to a lack of measuring equipment and other factors, but it did not make swords extremely heavy. As evident from surviving examples in museums, swords used in combat during the medieval and Renaissance periods were lightweight and agile.

During the Middle Ages, a guild system produced swords and assured quality standards. Later, the sword making at Solingen in Germany manufactured the best steel blades, equipping cavalry swords, broadswords, and rapiers.

Myth #2: Medieval and Renaissance swords were heavy and clumsy.

Sword fighting involves various techniques, grips, and blocks which vary depending on the type of sword. Those who lack proper sword training and experience handling real swords might find a sword exceptionally heavy.

Yet, in the hands of a martial artist, the same sword could be lightweight and well-balanced. Unfortunately, some modern fencers compare fencing weapons—foil, épée, and saber—of modern sport to historical swords and subsequently find the latter heavy and unwieldy.

Myth #3: Swords had to be extremely heavy to smash plate armor.

While a sword definitely has to have enough weight to deliver a forceful blow, it does not necessarily need to be extremely heavy and unwieldy. Earlier longswords were optimized for heavy cutting strokes. However, the improvement of full plate armor made smashing or cutting with a sword useless.

Therefore, later longswords became more sharply tapered and were designed for thrusting against vulnerable points in plate armor instead of trying to cut through it. More than that, smashing through full plate armor with a sword could damage the blade. There were also other weapons such as war hammers that could deliver more powerful blows.

Myth #4: A strong man should take a heavy sword to inflict more damage with the weapon.

Regardless of how strong or skilled a swordsman, a heavy sword would be tiring to wield after a couple of exchanges. A tired sword arm leads to weak, ineffective blows, inaccurate thrusts, and late parries. Hence, a sword should not be too heavy to remain an efficient combat weapon. Generally, a skilled swordsman, who keeps good control of his sword for a long time, has a better chance of winning a sword fight.

Myth #5: Medieval fighting styles relied on heavy swords instead of skills.

Some swordsmen, such as Egerton Castle, claimed that the fighting styles of the medieval period relied on brute force and heavy swords rather than skill. However, this belief likely stemmed from the perspective of Victorian fencers who disfavored the unsophisticated grappling techniques. Unfortunately, such claims resulted in the idea that medieval swords were extremely heavy in the public mind.

Myth #6: Only the warrior class was allowed to carry swords.

Throughout the Middle Ages, the right or custom to carry a sword varied according to region, period, and regulations. In medieval Europe, the knights and mounted men-at-arms used swords, though noblemen also used these weapons for self-defense.

In Japan, the samurai sword katana was exclusive to the warrior class. However, commoners of certain classes including townsmen and merchants were also allowed to carry a short sword called wakizashi.

Myth #7: Swords and armor were extremely heavy and impaired a wearer’s mobility.

An entire battlefield armor usually weighed between 45 to 55 lbs (20 to 25 kg), but its weight was distributed all over the body. Some specialized tournament armor was too heavy and likely locked its wearer in certain positions. However, such armor was designed for specific occasions and only worn for a limited time.

Also, swords were well-balanced and maneuverable weapons. By the 17th century, the widespread use of hand firearms led to the increasing weight of armor, with some heavy cavalry armor weighing about 77 lbs. (34 kg). At the same time, full armor became rare, and metal plates only protected vital body parts.

Historical Facts About Heavy Swords

Throughout history, swords functioned as deadly weapons for battlefield melees and close-quarter combat. Some types of swords had relatively heavy blades but not the excessive weight many would think. Here are the facts about historical swords and what made them lighter than they actually looked:

The size of the sword does not always determine its weight.

A sword’s weight cannot be judged solely by its blade length or width, as its blade form, cross-section, crossguard, and hilt design are also factors to consider. Also, a thinner blade does not necessarily mean it is more lightweight. Rapiers had slender thrusting blades yet generally weighed around 2 lbs. or more, with much of their weight concentrated in their hilts.

The so-called blood grooves lightened the blade.

The term blood groove is linked to the misconception that it could speed the blood flow from a wound, ensuring a fatal injury. Some also thought that stabbing creates a suction effect on the blade, and the groove could make the sword easier to withdraw.

Other theories state that these grooves retained poison to ensure the opponent’s death. However, they were actually designed to make the blade lighter without weakening its structure. They were common in several edged weapons, from European to Islamic and Chinese swords.

The pommel functioned as a counterbalance to the blade.

Generally, light pommels shifted the balance of the weapon towards the point, while heavy pommels moved the weight back towards the hand. Heavy pommels also made some swords, especially arming swords more maneuverable at the cost of reduced weight in the cut. Also, the crossguard’s length helped in distributing weight.

Too heavy swords are slow to change direction.

A sword had to have enough weight, but it should not be too heavy to the extent that they are slow to change direction. Technically, doubling the mass of a sword can provide twice the striking power. However, doubling the momentum of a strike also requires four times the effort. More than that, slashing cuts also need the sword to move a lot to develop momentum.

Two-handed swords have more leverage than single-handed swords.

A longsword, equipped with a two-handed grip, distributes its weight in both hands, making it feel more lightweight and maneuverable. Also, it hits a bit harder than an equivalent single-handed sword. On the other hand, a single-handed sword may be a lightweight weapon, but it also requires more effort on the swordsman’s hand, wrist, and forearm. In fact, controlling a rapier at the end of a fully extended arm is more demanding.

The weight and balance of swords are important aspects in martial arts.

In Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA), the weight and balance of historical swords are crucial to understanding their application in combat. The more a newly-made sword handles like a historical one, the more accurate the interpretations of the historical teachings would be.

The so-called battle-ready swords often have high carbon steel blades and very sharp edges, equally capable of delivering powerful cuts. Still, they must also be well-balanced, lightweight, and maneuverable.

Popular media and legends depict the sword as a mighty weapon.

In various legends and chivalric fiction, swords are often depicted as mighty weapons only heroes and gods can wield. In the Chronicles of Froissart, Sir Archibald Douglas wielded an immense sword no one else could wield.

Also, stage combatants and theatrical fencers are not required to wield swords in a historically accurate manner. Instead, they tend to favor flashy movements for the purpose of entertainment. Comparatively, historical sword fights often involved subtle but intense movements.

Some cutting swords were heavy enough to maximize slashing potential yet short enough to be mass-produced.

The langes messer was a single-handed sword suitable for shearing cuts. It represented a compromise between weight, length, and construction cost. The single-edged falchions also relied on heavy blades which swelled toward the tip for efficient slashing. However, they were too unbalanced to thrust well.

Conclusion

The seemingly heavy swords used on the battlefield were far lighter than most people realize. Though considerably heavier than their smaller counterparts, they have proved to be agile and lightweight weapons that remain an object of interest among collectors, enthusiasts, and military historians today.